Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Last time we re-lived the Willard Hotel’s early era, when it was run by brothers Henry and Joseph Willard and occupied a sprawling complex of low-rise 19th-century buildings on the northwest corner of 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW. With the death of Joseph in 1897, control of the hotel fell to his son, “Captain” Joseph E. Willard (1865-1924), who had big changes in mind. As the 20th century dawned, a new era and a new building were in store for Washington’s most prominent hotel, and there would be plenty of drama ahead as well. At one point the building was abandoned and left in ruins, but it finally took on a new life as the once-again grand hotel we know today.

The Willard Hotel, circa 1910 (author’s collection).

The younger Joseph, though born in the Willard, immediately began planning to replace it when he gained control of the property. He hired architect Henry Janeway Hardenbergh (1847-1918) to design a thoroughly modern new building. Hardenbergh had designed New York City’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and would soon be working on the Plaza Hotel there as well. For the Willard, he created a soaring Beaux-Arts palace that resembled in many ways his other Washington hostelry, the Raleigh. Sometimes called Washington’s first skyscraper, the new Willard used advanced construction techniques, including a steel frame and reinforced concrete base. The stately exterior finishes included rusticated Indiana limestone curtain walls on the first three stories with beige brick and terracotta detailing above. The highly-ornamented top-floor dormers, curved mansard roof, and bullseye windows have become iconic.

Construction took place in two phases so as to allow hotel operations to continue uninterrupted. The first part of the new hotel—the southern section on Pennsylvania Avenue—went up between 1900 and 1901, while guests stayed in the northern part of the old hotel opening on F Street. The hotel’s sumptuous new main lobby on Pennsylvania Avenue opened for business in October 1901. After guests moved into the new structure, the rest of the building went up between 1902 and 1904.

Like the Raleigh, the new Willard included a lavish ballroom and private dining room on the top floor with magnificent views of the city. At street level were the restaurants. The main restaurant on the first floor was “one of the largest and most elegant dining halls to be found anywhere,” according to The Washington Times. “With its richly decorated ceiling and great columns it is a sight worth looking upon.” Across the long main corridor, which in time would be called Peacock Alley, was the so-called Pompeian Room, a “dangerous” place in some people’s minds, because men and women could mingle there, and women were allowed to smoke. Overlooking all this activity was a balcony designed to accommodate the hotel’s in-house orchestra.

Continues after the jump.

The 10th floor ballroom arranged for a banquet. Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston (Source: Library of Congress).

The new Willard’s ballroom, dining rooms, and other public spaces were the place to see and be seen in turn-of-the-century Washington. The first time Mark Twain stayed at the new hotel, he supposedly went downstairs for dinner via the elevator and discovered that it provided an overly discreet way to get to the restaurant. Vexed by this, he promptly climbed back upstairs one flight and crossed over to the grand staircase in the front of the building, where he made a much more ostentatious descent and was besieged by legions of mostly female admirers, much to his content. All was right in the world.

The dining room, photographed by Frances Benjamin Johnston (Source: Library of Congress).

Of course, the opulence and snobbery were objects of ridicule as well. In 1910, a writer for the Kansas City Star penned this lampoon of Peacock Alley:

Peacock Alley, or Alimony Avenue, it may be stated for the benefit of benighted persons who do not live in Washington, is the corridor that runs through the Willard Hotel from Pennsylvania avenue to F street…. It is a gorgeous tunnel, carpeted in red, lined with gilded mirrors and hung with tapestries. The price tags have been removed from these articles, but it is believed the figures they bore were almost as large as those now on the dinner menus in the adjoining dining rooms.

Some haughty-looking chairs and divans, carved, upholstered and inlaid, stretch in front of the mirrors and invite such as feel they are worthy to sit on them. Opening off these exclusive and Oriental precincts are the dining rooms, in which aristocratic and expensively dressed waiters glide about among diners almost as aristocratic and expensively dressed, to the music of an expensive orchestra, playing the most expensive tunes to be heard anywhere….

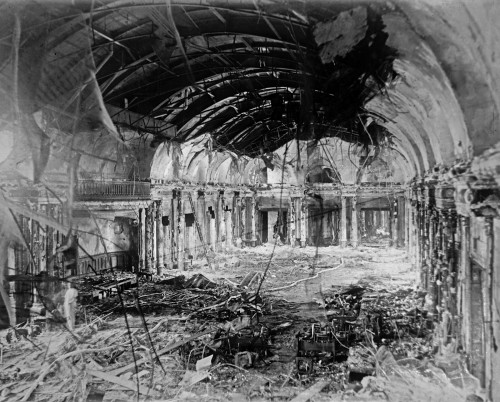

Late one night in April 1922, a devastating fire broke out in the top-floor ballroom, where just hours before the Gridiron Club had held their annual banquet. “Perhaps not in years has Washington seen so spectacular a fire,” the Washington Post commented. “Standing on a hill, the Willard is easily within sight of outlying portions of the city and when the flames ate their way through the roofing and leaped high in the air the gigantic torch made a spectacle that could be seen for miles.”

The 10th floor ballroom after the fire (Source: Library of Congress).

Miraculously, no one was hurt in the blaze. Guests were roused from their sleep and hurried downstairs, where many enjoyed an early breakfast. The hotel graciously kept the elevators running for a full half hour after the fire was noticed so that guests would not have to use the stairs. The fire department eventually put a stop to this exceedingly dangerous practice, but only after it was noticed that “the flames started eating their way down the [elevator] shaft.”

The hotel had been filled to capacity, with many notable guests attending the Gridiron Club dinner or an assembly of the Daughters of the American Revolution that was also underway. Vice President Calvin Coolidge and his wife Grace were living at the hotel at the time, and were among those roused from their sleep by the commotion. Coolidge remained unfazed by the incident, socializing in the lobby and passing out cigars to newspapermen. In the end, the damage from the fire was cleaned up, the great ballroom rebuilt, and the Willard saga went on.

As a luxury hotel, the Willard struggled during the Great Depression but managed to stay afloat. In 1930, a decision was made to save money by eliminating the dining room orchestra, but there was such a hue and cry from wealthy patrons that a new, much-smaller orchestra was reinstated at a sharply-reduced cost. Nevertheless, amidst the economizing, improvements and modernizations continued. In 1934 air conditioning was installed, and in 1937 bathrooms were added in every room. When the war years came, business suddenly boomed, and it became hard to find a room at the Willard. Several floors were leased out to the British government and other war-related agencies.

A matchbook cover from the 1950s (author’s collection).

Various management companies had been running the hotel for many years, and in 1946 the Willard family decided to sell the hotel to Louis Berry’s Abbell hotel chain, which had also taken over the Raleigh. In retrospect, it seems like a fateful turning point. The institution was headed for a tailspin.

Despite extensive remodeling in the 1950s, the Willard was more an “old man” than a grande dame among Washington hotels; the Mayflower, Statler, Shoreham, and Wardman Park all were newer and located in more fashionable areas. By the 1960s, bookings were in decline. The Willard’s old rival on the avenue, the Raleigh, closed and was torn down in 1964. That same year, the President’s Council on Pennsylvania Avenue, commissioned by John F. Kennedy to find ways to spruce up the dilapidated thoroughfare, issued its report, calling for the Willard (along with the rest of the block, including the Hotel Washington) to be leveled and replaced by a vast, barren National Square. “If built to the Council’s recommendations it is believed that this will be the first truly urban, truly national, square in the United States,” the report exclaimed. Though Congress didn’t set aside any funds to carry out the plan, it won the approval of the National Capital Planning Commission as well as the Commission of Fine Arts. The Willard’s days appeared to be numbered.

With patronage down and the government wanting to raze the building, the Willard’s last straw came when the April 1968 riots precipitated a swift and dramatic decline in the old downtown. In July the hotel abruptly shut down with no advance notice. Bookings were canceled, guests sent on their way, and staff laid off. From veteran employees who had spent their careers at the hostelry to the bartender who had been hired the previous day, all were suddenly out of work.

The Willard lobby in 1969, before the big sale of furnishings and fixtures (Historic American Buildings Survey).

As Richard and Marie Carr have explained, the closing of the Willard, abrupt as it was, seems to have struck a chord with the public, and many people began to reconsider how important it was to the city’s heritage. Particularly troubling was the no-holds-barred fire sale of all the hotel’s fixtures and furnishings, held in October 1969. “Thousands of souvenir hunters and nostalgic shoppers thronged to the doomed Willard Hotel yesterday looking for bargains,” the Evening Star reported. The selling went on for several months. By December the Star was reporting on people coming in to buy anything and everything they could get their hands on—pieces of oak molding from doorframes, marble panelling from bathrooms—it was all for sale: “Two girls emerged from the elevator into the columned lobby, dragging a yard-square hunk of grey marble. ‘Who do we pay for this?’ asked the shorter brunette with the brick hammer in her hand. ‘Is there anyone who can help us get it into our car?'”

Even before the old building was stripped, a protracted struggle was underway over what to do with it. At one point the General Services Administration suggested a land swap: unwanted federal property—Miller Field on Staten Island or the old Navy barracks on Columbia Pike in Arlington—in exchange for the hotel. Negotiations dragged on for years but ultimately went nowhere. The hotel’s owners, two investors from New York and California, became frustrated and filed suit in 1969 for the right to tear down their empty hotel and replace it with an office building. The Fine Arts Commission blocked that option as incompatible with the Pennsylvania Avenue Plan.

A stairway photographed in 1976 for the Historic American Buildings Survey.

The owners then attempted further legal maneuvers to win the right to either tear down the building or radically alter it, none of which succeeded. A key player was Don’t Tear It Down, predecessor of the D.C. Preservation League, which was fresh from a successful battle to save the Old Post Office. The group intervened in 1974, when the Willard’s owners won a court ruling allowing them to remove the facade and convert the structure into a new office building. Acting in the nick of time, Don’t Tear It Down successfully sued to delay the destruction, a move that turned out to be crucial in buying time to find a way to preserve the venerable building.

The empty building in the 1970s, photographed for the Historic American Buildings Survey.

By late 1974, key government agencies such as the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation and the National Park Service had had a change of heart and came out in favor of saving the Willard. A study was commissioned that showed the building could be restored to service as an historic hotel. More legal maneuvering ensued, but finally in 1978 a settlement was reached whereby title to the hotel was transferred to the PADC for $8 million.

Restoration work photographed by Carol M. Highsmith (Source: Library of Congress).

Once the building was safe from destruction, a gargantuan task lay ahead to restore it to its former glory. Not only had it been thoroughly stripped of interior fixtures, it had also suffered extensive damage from more than a decade of complete neglect and needed extensive modernization to function as a luxury hotel. After some false starts, the Oliver T. Carr Company was selected in 1981 to lead the restoration work, which included adding new adjacent office space to make the project financially viable. Ironically, the Carr Company began its first-class restoration job on the Willard in 1984, the same year that it demolished the historic Rhodes Tavern just a block away. Carr, though committed to a sensitive restoration of the Willard (under the strict guidance of the PADC and the National Park Service), had stubbornly resisted years of effort by preservationists to save Rhodes Tavern, a modest building that was arguably the more important landmark of the two.

The refurbished Willard photographed by Carol M. Highsmith (Source: Library of Congress).

The Willard reopened in 1986 to much critical acclaim as the Willard Intercontinental, once again one of Washington’s most glamourous hostelries. Writing in the Washington Post, Benjamin Forgey likened the stepped modern office pavilions on the west side of the historic building to “baby elephants following the star performer into the ring.” Perhaps more importantly, he thought the restoration of the historic parts of the hotel had struck a judicious balance between strict preservation and the necessities of a modern hotel. For two and a half decades since that time, the restored Willard has proven enduringly successful in a revived and transformed downtown.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included: Richard Wallace Carr and Marie Pinak Carr, The Willard Hotel: An Illustrated History (2005); Dean R. Montgomery, “The Willard Hotels of Washington, D. C., 1847-1968” in Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Vol. 66/68 (1968); National Capital Planning Commission, Downtown Urban Renewal Area Landmarks (1970); The Report of the President’s Council on Pennsylvania Avenue (1964); documentation for the National Register and Historic American Buildings Survey; and numerous newspaper and magazine articles.

Recent Stories

Photo by Clif Burns Ed. Note: If this was you, please email [email protected] so I can put you in touch with OP. “Dear PoPville, Hey – you stopped me while…

Unlike our competitors, Well-Paid Maids doesn’t clean your home with harsh chemicals. Instead, we handpick cleaning products rated “safest” by the Environmental Working Group, the leading rating organization regarding product safety.

The reason is threefold.

First, using safe cleaning products ensures toxic chemicals won’t leak into waterways or harm wildlife if disposed of improperly.

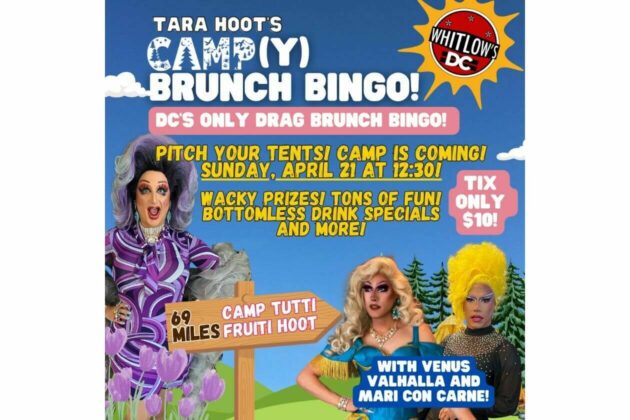

Looking for something campy, ridiculous and totally fun!? Then pitch your tents and grab your pokers and come to DC’s ONLY Drag Brunch Bingo hosted by Tara Hoot at Whitlow’s! Tickets are only $10 and you can add bottomless drinks and tasty entrees. This month we’re featuring performances by the amazing Venus Valhalla and Mari Con Carne!

Get your tickets and come celebrate the fact that the rapture didn’t happen during the eclipse, darlings! We can’t wait to see you on Sunday, April 21 at 12:30!

Frank’s Favorites

Come celebrate and bid farewell to Frank Albinder in his final concert as Music Director of the Washington Men’s Camerata featuring a special program of his most cherished pieces for men’s chorus with works by Ron Jeffers, Peter Schickele, Amy

Cinco de Mayo Weekend @ Bryant Street Market

SAVE THE DATE for Northeast DC’s favorite Cinco de Mayo celebration at Bryant Street NE and Bryant Street Market!

Cinco de Mayo Weekend Line up:

Friday, May 3: